Oleksii - stock.adobe.com

The wide web of nation-state hackers attacking the U.S.

Cybersecurity experts weigh in on what it means to be a nation-state hacker, as well as the activities and motivations of the 'big four' countries attacking the U.S.

The threat of adversarial foreign governments using their hacking might to infiltrate and gather intelligence from the United States is a tale at least as old as the modern internet, but in recent years, nation-state hackers have been brought to the forefront of the cybersecurity industry's collective mind.

In December, threat actors working on behalf of the Russian government conducted a supply chain attack against the software company SolarWinds, based in Austin, Texas. The attack compromised updates for the company's Orion IT management platform, and these updates, when released to its customers, ultimately compromised many organizations across the public and private sectors, including U.S. government agencies.

The fallout of these attacks remains ongoing, most recently with sanctions brought against Russia and private-sector companies that work with the Russian government.

And in early March, Microsoft disclosed the mass exploitation of on-premises Exchange servers via four zero-day vulnerabilities and attributed the exploitation to a Chinese state-sponsored group named Hafnium. The exploitation quickly escalated into activity from numerous threat actors, both state-sponsored and non, and the ProxyLogon attacks (named after the main vulnerability disclosed in March) have compromised tens of thousands of organizations across the world.

But nation-state activity doesn't end there. Headlines about state-sponsored hacking against the U.S. have appeared on a monthly -- if not weekly -- basis for years, and the motivations behind these attacks can vary widely. And as both the SolarWinds supply chain and Microsoft Exchange Server attacks have shown, the targets are no longer limited to federal agencies and the largest companies. Enterprises of all sizes are now at risk, whether it's ransomware or a data breach.

Defining the nation-state threat actor

Defining what a "nation-state threat actor" is may seem like a simple task: a hacker or group of hackers working with an adversarial government that commits acts of cybercrime against the U.S. or its allies. But defining who nation-state actors are, what they do and what their motivations are becomes a more complicated task.

Recorded Future COO Stu Solomon told SearchSecurity that the concept of a nation-state threat actor is often conflated with the idea that it's someone in the direct employ of a government doing their direct bidding, but in reality, it's not so simple.

It can include those in a government's direct employ, like the military or a government agency. Nation-state activity can also come from government contract work, or from cybercriminals working under "government acquiescence, if not government sponsorship and direction," Solomon said. This includes situations where groups of cybercriminals who aren't sponsored by a government normally will work with the government on various national objectives in order to be allowed to continue their cybercrime.

Nation-state threat activity can involve advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, which are typically under government employ and focus on longer-term cyber attacks where the threat actors gain access to a network and remain undetected for a prolonged period of time. This isn't just limited to adversaries, either -- many nations across the globe have developed offensive cyber operations, and the U.S. has at least one of its own.

However, not every APT or "sophisticated" threat actor is a nation-state hacker. And in defining anything about nation-state threat actors, the most important phrase to remember is "it depends." More specifically, it depends on which nation-state is being discussed.

In terms of attacks on the U.S., nation-state threat actors typically (but not always) come from the "big four": China, Russia, North Korea and Iran. Each government has different structures, circumstances and motivations that define the form their activity against the U.S. takes.

The motivations of the big four

Overwhelmingly, the primary goal of nation-state activity is to gather information, CrowdStrike senior vice president of intelligence Adam Meyers said.

"Their intentions are intelligence collection, sabotage, disruptive and destructive attacks, and then this concept of what we call OPE, or operational preparation of the environment. Which is to say, in a future conflict, if a foreign adversary wanted to be able to turn off the lights or disrupt the water or do something like aid in an armed conflict, that they would effectively set those hooks now so that later they can leverage that activity and capability."

That said, different departments and operations within a nation-state can have different goals, and state-sponsored activity can also be conducted for unrelated military, political and financial reasons. For example, North Korea is unique among the big four in that it includes fundraising as part of its national cyberstrategy.

"The only country that has really structurally incorporated financial gain into their financial cyber operations is North Korea. If you look at the structure of North Korea, they have this so-called 'Third Floor' where they've got these offices that are responsible for generating cash for the regime. And so North Korea fits into a slightly different model there," Meyers said.

The Third Floor references three North Korean offices operating under the Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea. One of the three, Office 39, is dedicated to fundraising.

Solomon said that North Korea does this in order to further their goals for national independence, as well as conducting military research and development, including weaponry, and circumventing sanctions. He added that while North Korea is an unusual case on the large scale, other countries have benefited from the money obtained in cybercrime.

"You will see that in other countries that are economically depressed all across the globe in Eastern Europe, in South America, [and] in areas where it almost becomes this cottage industry where you have this acquiescence of the government in order to fuel the local economy," Solomon said.

Iranian threat actors have also been conducting ransomware operations, but Meyers said that it appears to be hackers operating off-book and not part of the national cyber-offensive strategy. As for what is part of Iran's national strategy, Solomon explained that their focus is on investing in cyber capabilities for regional conflicts and power projection.

"If you get into a saber-rattling issue, say, between Iran and the U.S., it's a great way to reach across the vast Earth and create an impact without it being kinetic, and being able to control the proportional response in the face of a military you probably don't want to get into direct conflict with," he said.

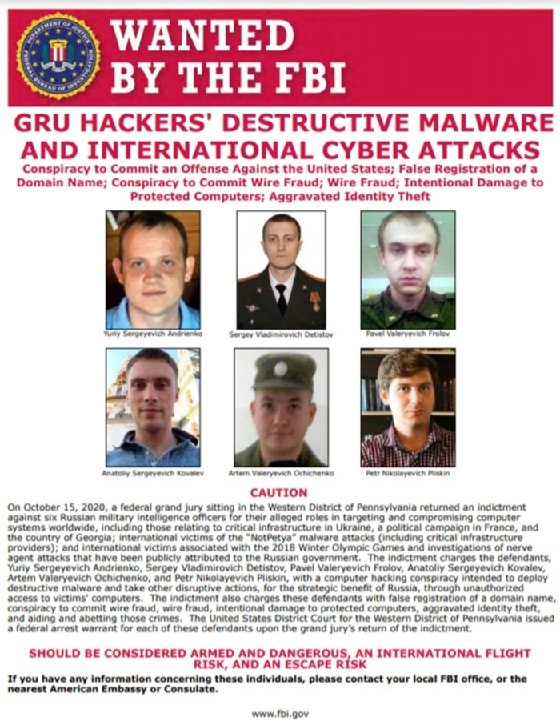

Russia, meanwhile, uses its cyber operations as "an apparatus of national power," Solomon said, with its high investment, high sophistication activity carefully aligned with military, political and intelligence interests. Beyond intelligence, Russia has conducted election influence and interference operations against the U.S..

Lastly, Solomon said that China is remarkable in that, due to their Five-Year Plans, it's possible to somewhat predict where the country will apply its cyber capabilities. Since the initial plan was released in 1953, these plans have been issued by China to show the nation's overall focuses for the next half-decade.

The plans set targets for various industries and areas of improvement within China, and as an article by workforce development vendor CyberVista explained, "When you step back and examine previous victims of Chinese cyber attacks through the lens of China's [Five-Year Plan], it becomes distinctly clear that targeted companies and industries victimized by Chinese hackers align with the areas of need, investment, or improvement articulated in the FYP."

Also particular to China, Solomon said, is how its activity utilizes every cyber-capable part of its society.

"What's interesting about the Chinese cyber capabilities is that it really is this complete blend of individuals, students, hackers, military members in uniform, intelligence people in government employ, and government officials themselves," he said. "It's kind of the totality of the ecosystem that they bring to bear, which really blurs the line between who's doing what at any given time. There's so many different groups that are called upon across the entirety of their society to participate in their cyber mission."

Chinese threat activity against the U.S., in particular, has a lengthy history. Starting in 2003 and into the mid-2000s, a group of state-sponsored hackers conducted attacks against the U.S. and U.K. governments as well as a series of defense contractors. The hackers, as well as the activity, were given the name Titan Rain by the U.S. Since then, Chinese nation-state hackers have been responsible for a number of incidents, including the 2015 breach of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management and the more recent Equifax breach in 2017.

How individuals hack for nation-states

Because of the large number of situations and contexts that can define nation-state threat activity, the circumstances that lead individuals to commit such attacks depend on many factors, including and especially the nation-state itself.

Overall, the people that make up nation-state hackers can include individuals who are hired, conscripted, compelled, contracted or recruited from school. Their social and financial circumstances, as a result, can also greatly vary.

For example, CrowdStrike's Meyers pointed out that North Korean hackers tend to have a higher quality of life relative to the rest of the country. "North Koreans get indoctrinated at a very young age and are pulled even out of middle school level" in order to build cyber skills, he said. Chinese hackers, meanwhile, are often recruited out of universities. In Iran, hackers are typically conscripted or compelled.

Meyers emphasized that "country by country it differs -- there's no one-size-fits-all."

Recorded Future's Solomon said that Russia has spent years building "a pipeline of talented individuals to conduct operations on behalf of the government." Reportedly, this pipeline has included university students, cybercriminals and civilians.

In general, Solomon said, intelligence and military roles are paid in line with government employees, and that those involved in ransomware -- whether as part of government business or not -- can become very wealthy.

Attribution and hacking back

From an attribution standpoint, Meyers said that CrowdStrike takes the intentions, capabilities, targets and tools used into account when determining whether activity is more in line with nation-states, cybercriminals or hacktivist groups.

For example, he said, the first step is to categorize a cyber incident; was the cyber attack motivated by financial gain, intelligence collection, geopolitical or national objectives, or hacktivism? Hacktivism can be conducted by a spectrum of actors, from animal rights and social groups to nationalist and terror groups.

Financial and political motivations can overlap from time to time and, as Solomon pointed out, threat actors purposely attempt to obfuscate their identity and affiliation -- often through common and/or shared infrastructure and techniques. Because of reasons like these and others, "attribution is really, really hard," Solomon said.

In the SolarWinds supply chain attack, for instance, Russia was only publicly suspected of involvement until last week, when President Joe Biden signed an executive order with new sanctions against the Russian government, formally attributing the attack to the country's foreign intelligence service.

Solomon said that from a defensive position, there are more important aspects of an attack than determining who did it.

"I think it's more important to understand the tools that are used, the capabilities and the telltale signs around them when you're on the defensive side of the house. Rather than who, it's important to understand how and with what. That's something I think is very important when you're talking about these nation-state scenarios," Solomon said.

When attribution is made, the question of how a government, particularly the U.S., is supposed to respond has been up for debate in the wake of the SolarWinds attack. A 60 Minutes segment in February featured several interviews that advocated for "hacking back," or launching an offensive cyber attack against the assailant.

Kevin Kline, Aggeris Group COO and former assistant special agent-in-charge at the FBI's New Haven, Conn., field office, told SearchSecurity that hacking back would only make sense in circumstances where the benefits justify the action.

"In any sort of conflict, you need to be both offensive and defensive. And sometimes the best defense is a good offense. When is [hacking back] the right move? It's the right move when it can be done for a purpose that significantly outweighs the negative," Kline said. "In other words, we can reverse-hack at any time. Our capabilities are really good. But at the same time, what we don't want to do is have that attribution, and we also don't want to give up our techniques."

When the topic of governments hacking other governments comes up, so do concerns about potential escalation of attacks against critical infrastructure that result in significant loss of life.

In March, SearchSecurity spoke with multiple critical infrastructure and cybersecurity experts about the potential for such attacks in the wake of the Oldsmar, Fla., water treatment plant hack. While critical infrastructure attacks are on the rise, experts said, and while dangerous breaches have occurred, no mass-casualty cyber attack has been reported to date.

There is currently no code of ethics for nation-state cyberactivity and no rules or treaties like the Geneva Convention for cyberwarfare. However, a cyber attack that intentionally and successfully causes loss of life would likely be treated as a kinetic action, and may be at risk of a similar, if not escalated, response.

This may well be a mitigating factor, because as Kline points out, such an extreme action would get in the way of what nation-state threat activity is primarily used for: intelligence.

"The ultimate goal of all the activity is one of two things: it's either to get info or money," he said. "The unwritten rule usually is, if they're doing anything that is going to take that away, they're not going to do it."

Alexander Culafi is a writer, journalist and podcaster based in Boston.